We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.

– Anais Nin

One evening somewhere in the Northern India, a farmer is making his way back to his village from the fields. In his hand he carries a lantern, it’s flickering wick barely illuminating his path. As he comes around the bend towards the path leading up to the village he catches sight of a snake.

Dark and quiet it appears to slither into the path and settle in the middle. Instinctively the farmer freezes and gets quiet. He backs up slowly hoping that in a minute the snake will cross and he’ll continue. Beads of sweat gather on his forehead.

After what feels like an eternity he creeps back around to see if his slithering friend had moved on. Dread fills him as he sees the shape firmly perched in the same place. He realizes that he’s going to have to find another way. Looking around he finds a stick and musters up his courage. Taking a deep breath he steps forward his lantern thrust forward like a saber, the stick raised in the other hand.

As he lands right in front of the snake he finds a harmless inert piece of rope. In an instant his fear is replaced with laughter. Relief floods his body as a smile accompanies him on the rest of his journey home.

If you’ve lived any amount of time then misperceptions are a common part of your experience. While we may not encounter ropes masquerading as snakes on our path home, we do experience all manner of misfirings in our everyday life. An unrelated grimace on a boss’ face feels certainly tied to the email we’ve sent her.

How does perception – a process that mediates our experience of the external world – actually work?

What is perception and how does it work?

Perception is how we make sense of the external world – specifically it’s how we select, organize, and interpret the sensations that we encounter. Sensations are the result of our specialized neurons (called sensory receptors) encountering stimuli and is a physical process. Perception is the interpretation of those sensations based on our memories and expectations. For eg: the smell of coffee might be a sensation, but the feeling of coziness might be a perception based on our history with the smell.

Credit: Mpj29

Not all sensations are perceived

In each moment our brain encounters a flood of sensations and has to be discerning about what is actually processed. There is a whole field of study (called Signal Detection Theory) that examines what it takes for a stimuli to be detected. By some estimates the human body sends the brain 11 million bits of input every second (10M of that is from our eyes). Our conscious minds however can only process about 50 bits of information per second. Predictably this results in a bottle-neck – how should the brain decide what makes it to conscious attention and not! Even so there might be something happening that requires faster attention than our conscious minds can respond to adequately (it takes a half second between getting the stimuli and us knowing about it). To handle this we have a reflex system that can respond in less than a 10th of a second.

Filtering out stuff that doesn’t change

One strategy our brains use is they filter out stimuli that remains constant. This allows us to focus on just the changes and evaluate it to see if it’s helpful or harmful. There is a small structure in the brain about 2 inches long and as thick as a pencil at the top of the spinal cord called the ascending arousal system (or Reticular Activating System) which plays a key role in this process. This is why after 15 minutes after first applying perfume we can no longer smell it as vividly.

Focusing on what matters

The brain also filters out the important information and increases its priority. An example of this is the cocktail party effect where you magically hear your name in the background din of conversations that was previously unintelligible. Our brain plays the role of a helpful assistant focusing and highlighting stimuli that might be helpful for us. If you’re expecting someone you start to hear the knocks on the door – sometimes even when there aren’t any! As we’ll see this anticipatory and predictive property of the brain can be wrong. Sometimes in strange and significant ways.

Perception is utilitarian

Our perceptual system interprets the data to help make sense of it. This perceptual expectancy, also called the perceptual set, is a tendency to see things in ways that match our view of the world. A simple example of it is that we read misspelled words with ease because we know what to expect

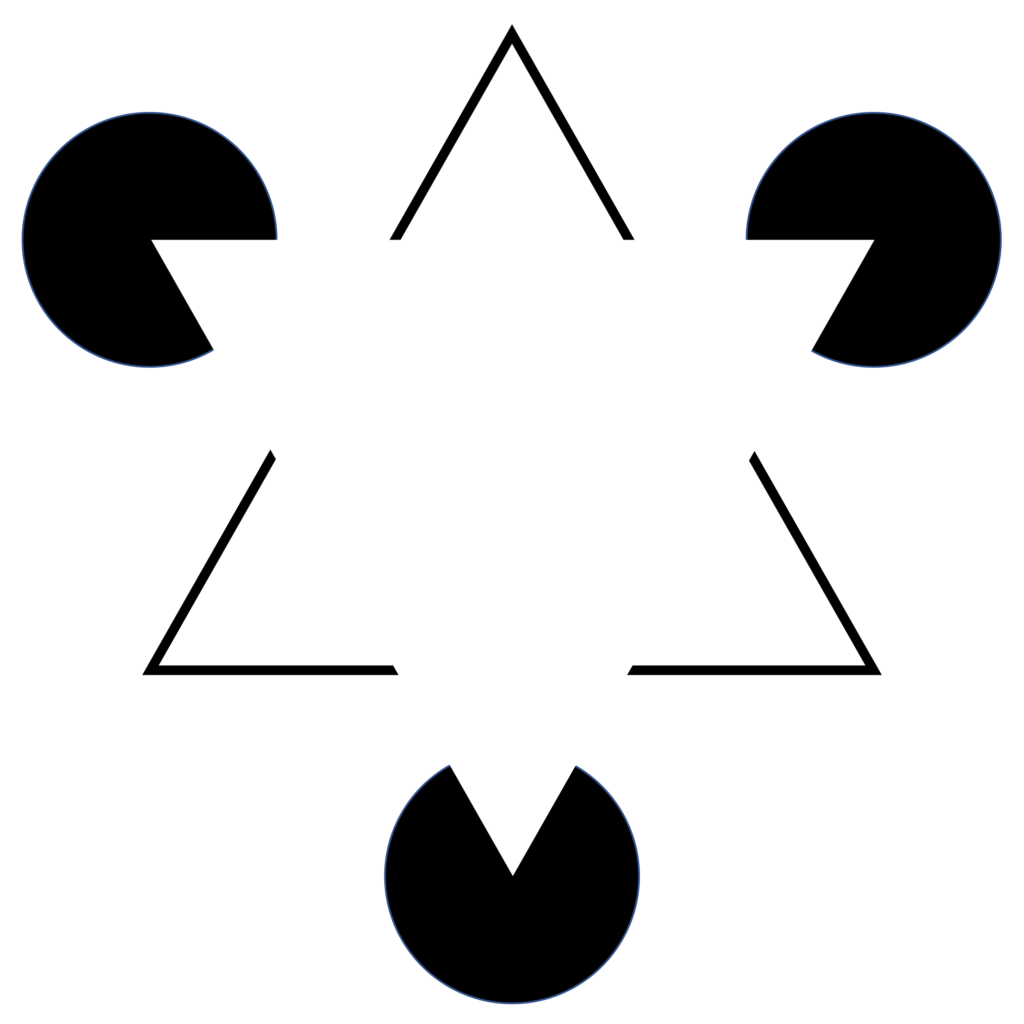

We also tend to see shapes faster probably because we live in a world of shapes. But alas we also see them when they don’t exist.

We live in a 3-D world and when we encounter 2-D information we convert it into a 3-D shape. In the Penrose triangle example we can’t shake the idea of a 3-D triangle even if the shape doesn’t make sense.

But we get tripped up at times

Sometimes there could be multiple interpretations for a given input. A classic example is Rubin’s vase where we can see a vase or a face. These are simple examples and there are many additional ones that show how our perception is guided by our expectations.

Credit: Mlechowicz

Perception is story-telling: How we interpret what it means

Perception isn’t a passive reception of the world’s input that we rationally analyze. Perception is an interactive activity. We’re participants in how we make senes of the world.

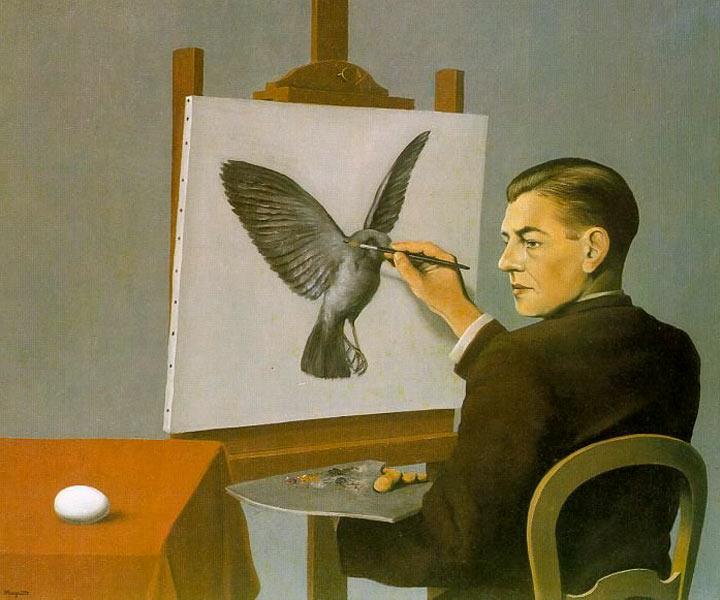

Beholder’s share:

In art history there is a concept called beholder’s share which means that the best art includes the user in its interpretation. If you see an impressionist painting it’s just blobs of paint up close, but we see a field of haystacks as we step back. The theory goes that if the participation is trivial then we’re bored by the art but if the level of participation is beyond our perceptual set (perhaps like some modern art) the viewer can no longer participate.

Do we see the world as it is?

The idea that things exists even when we don’t perceive them is called realism. The world has yellow coffee cups on tables and we come across them as they are (this view is called naïve realism). A nuance to this view point is that objects exist but they have primary properties (shapes, size, etc) and secondary properties (colors, smells, etc). This view called scientific realism says that in order for a yellow coffee cup to exist it requires a viewer who sees the table from a certain position (the light from the sun filtering in through the window blinds on an Autumn day) and a set of experiences on yellow (having seen and experienced yellow objects before).

Is there smell without a nose?

Most of us look around the world and see it in rich colors and contrasts. But we also know that the colors are just wavelengths of light perceived as blue or red. Fundamentally color is a perception and not an innate quality of light. Our biology and perception also makes it impossible for us to perceive certain wavelengths of light. For eg: reddish-green. Physically we perceive this color as brown. The receptors in our eyes for light on the red wavelength are canceled out by the receptors that detect green.

Perception of time: We see the world as it was

In the discussion so far we have not accounted for the passage of time. After all by the time we’ve seen the steam from the coffee cup it’s already floated away from us. In everyday life the disconnect between what we see and the actual state is slight. But if we look up at the night sky, the light from the stars has taken a long time to get to us. So long that in some cases those stars no longer exist. We see the world then as it was millions of years ago.

Perception of space: Is it 3-D?

We take for granted that we live in a 3-D world but how do we know that for sure? The image formed of the world in our eye is after all a 2-D image. In fact we’re not born with depth perception – it’s only around the fifth month do the eyes and brain learn to perceive a 3-D world. Our brains take cues from the 2 images we have to build a 3-D perception from a 2-D visual.

Seeing for survival

From an evolutionary perspective the interpretation succeed if we’re able to navigate the world and pass on our genes by reproduction. So is it better to see the world as it is? Or to see it in a way that ensures the propagation of our genes? Donald Hoffman, a cognitive scientist at UC Irvine has constructed evolutionary simulations to answer this question. In his simulation organisms compete for resources but have perceptual systems geared towards either seeing the true reality or perceptual systems that aid fitness (ability to perceive in a way that aids survival). And overwhelmingly the systems geared towards survival succeed.

Is reality a shared hallucination?

If what we see is just an hallucination then is it really there out there? We’ll cover this in a future chapter. But from a perception perspective, the hallucination we all agree upon is our reality – a common understanding what’s out there.

While most of us see just 3 colors there are rare individuals who are tetrachromats (able to see 4 colors). Where we see dull grays a tetrachromat would see rich colors. In addition to the physical differences in our sensory receptors the brain structure could enable us to perceive differently. For eg: in synesthesia, the pathways in our brain for one sense trigger another. Synesthetes would see numbers in color or feel shapes in the food they eat.

In these cases we can understand experience but what if it didn’t make sense to us. Would these people be labeled as crazy or mad?

How do we perceive ourselves?

If we don’t see the world out there as it is what about our perception of ourselves? Do we see ourselves as we are? Our brain has a model of our physical body called a body schema that it maintains. This schema is constantly updated from the various inputs coming into our brain. As we navigate the world our schema expands to include the tools and objects we handle. When we’re in our car we tend to have a sense of how far the car extends around us in space. When taking a turn we have an intuitive sense how much space we need. Driving a rental takes extra attention since our schema doesn’t have a full sense of the dimensions of the car.

Like the visual illusions we saw earlier, there are interesting body perception examples that illustrate the nature of our brain. The Rubber Hand Illusion is one which shows how our perception of ourselves can be fooled. In this case (see video below) a subject’s hand is covered and a rubber hand is placed in front of her. The experimenter strokes the rubber hand and the real hand at the same time with a brush. The brain now has to make sense of a signal – the eyes see a fake hand being brushed but the body is experiencing the sensation at about the same place. The brain starts to believe that the fake hand is actually part of the body. This is called proprioceptive drift as the schema seems to extend to the fake hand. Now when the experimenter pulls out a hammer and strikes the rubber hand the reflex reaction reacts as though the real hand was being struck.

The rubber hand illusion is an example of our brain attempting to understand the world by combining information from our visual, touch, and proprioceptive (our sense of where our body is) fields. The visual field and the touch sensation are combined to understand the world. This experiment has been repeated to find the points where the illusion stops. For eg: if the fake hand is too far away then the brain is no longer fooled. There have been experiments that have demonstrated this illusion can occur in other areas. In the dental model illusion, experimenters were able to convince subjects that a model of the mouth was their real mouth.

Buddhist view of perception

As we’ll see in future chapters perception and the interaction of consciousness and perception play a big role in the understanding the functioning of the mind. In the Buddhist view there are 6-sense doors (visual, olfactory, gustatory, tactile, auditory, and mental).

Key Points

- Our perception is utilitarian. It has evolved to serve us as navigate the world. The goal is to help us not show us what’s real in the world.

- We sense a 3-D world that is constructed out of a 2-D image. We sense a temporal world in the same way.

- Our perception of our physical self isn’t quite accurate either. It shifts and changes.

- We can’t really say for sure what the external world is really like.

Sources

- https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-psychology/chapter/introduction-to-perception/

- Dan Ariely Ted talk

- Encyclopedia Brittanica